Gender and Colour in Art History

The history of the colour blue and its association with masculinity isn’t quite as linear as you might think. Nowadays, despite the ever forward-moving progress being made, as a western society we still often align ourselves with the idea that blue is for boys and pink is for girls. In writing that sounds outdated, and yet we see this concept in motion all the time.

Blue is Not Just for Boys

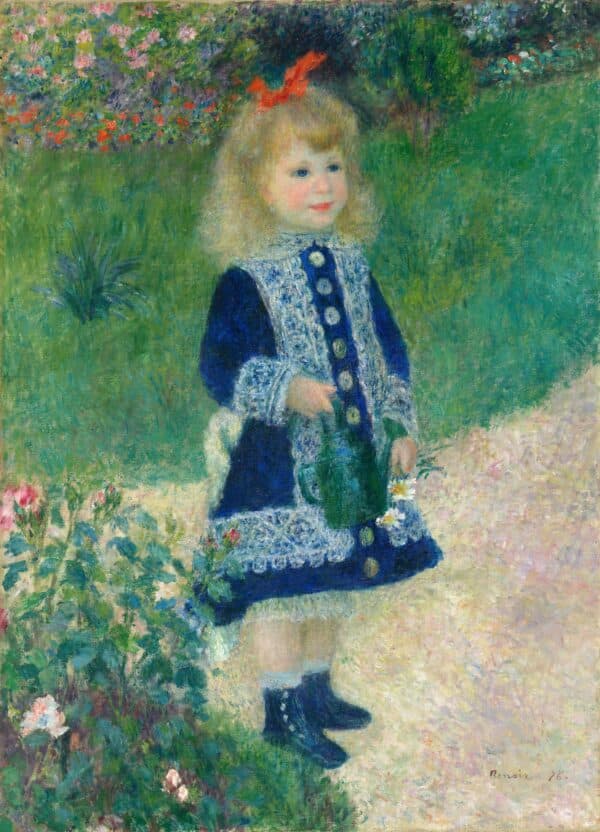

A girl with a watering can, 1963, Renoir

However, blue has not always been for boys. In fact, colour being assigned to gender is a relatively modern concept, as Joanne Meyerowitz advises in her text ‘A History of Gender‘ that it wasn’t until the 20th century that the term ‘gender’ was applied as a definition.

In Historian Jo B. Paoletti’s book Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America, Paoletti discusses how pre-1940s it was believed that pink was the stronger colour and therefore a better choice for boys. Whereas blue was considered dainty and feminine. For much of history the first choice would have actually been neutral white clothing that could easily be bleached and reused.

It wasn’t until the 1940s in America that children were being dressed in the ‘gender-typical’ colours we know today. The palette was slowly shifted by retailers and marketers, and so parents, concerned by the possibility of their children being perceived incorrectly, went with what they were told/sold. Given the nature of globalisation it is unsurprising how the rest of the western world followed suit.

Women in Blue throughout Art History

With this new context in mind we must consider the way art was created and viewed before c.1950. They might not have looked at an artwork with the preconceived idea that blue is a masculine colour. Nor would Old Masters have dressed their sitters in pink simply to connote femininity.

When looking at iconic depictions of women it becomes clear how frequently blue is used:

Firstly we have the elegant, virginal women painted by Vermeer, many of whom are adorned in blue and yellow. The most famous having been accessorised with a pearl.

Girl with a Pearl Earring, c. 1665 Vermeer

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

The Umbrellas

c. 1881-6

Oil on canvas, 180.3 x 114.9 cm

The National Gallery

Next, the female subjects of Renoir, Monet and Manet who didn’t use colour to define gender but to express their impressions of light, movement, mood, depth and form.

Woman with a Parasol, Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875, Monet, National Gallery of Art

Finally, we have the Madonna – a poster-girl for the colour blue. In almost every one of her portraits she is dressed in Marian ultramarine. Something that had nothing to do with her gender but rather her virginity and divinity.

The Alba Madonna, c. 1510, Raphael

The list could truly go on.

Blue Boys and Men

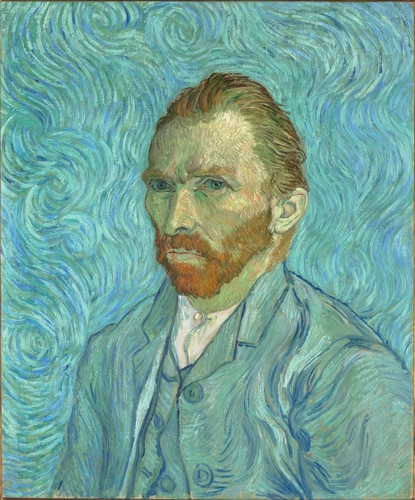

Naturally we also have famous paintings of men dressed in blue such as Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy and Vincent Van Gogh’s Self Portrait. But even works such as these have been studied and commented on with regard to the discourse of gender identity.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy, 1770

Vincent Van Gogh Artist Self-Portrait, 1889 © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

The point being the colour blue has and should always be worn and celebrated by all genders. For – as many artists have repeatedly recognised in their own journals and notebooks – the power of colour can reach far beyond the limits of what, or who, is being portrayed.

“Colour! What a deep and mysterious

language of dreams.”

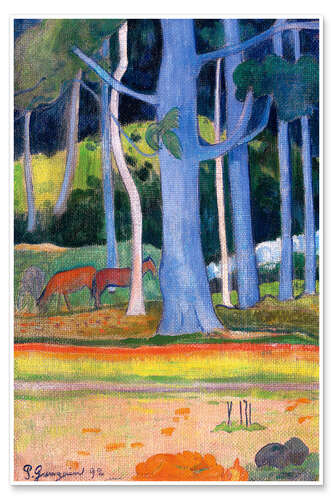

-Paul Gauguin

Blue is not a Gendered Colour

In conclusion: blue is for everyone. It can be masculine, feminine, neutral and everything in between. As we know, this is a concept that is as true in everyday life as it is in art history.

As we celebrate the colour blue and the marriage of blue and white in our collections we will continue to create products for everyone to love and enjoy!

“If you see a tree as blue, then make it blue.”

-Paul Gauguin

Landscape with blue trunks, 1892, Paul Gauguin