Clouds, a Canvas in the Sky

Cloud Study, Hampstead, Tree at Right, John Constable, 1821, oil on paper laid on board, red ground. Image credit Royal Academy

Clouds are mysterious and ephemeral aerosols, each one a visible mass of condensed watery vapour.

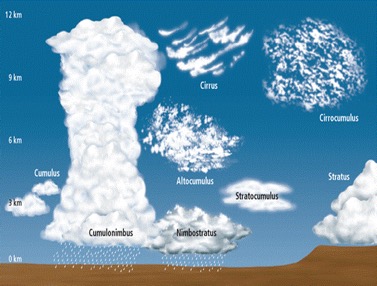

It was the amateur British meteorologist, Luke Howard, who created the name clouds that became universally adopted, so becoming known as the father of meteorology. His curiosity was born from daily musings on the different shapes of clouds he saw as he travelled to work by horse and carriage. In 1802, he presented his paper naming and classifying clouds to the Askesian Society, a debating club for scientific thinkers in London. It was published that year. Howard named three basic types of cloud, which are still in use today: Cirrus, Cumulus and Stratus. He also had names for identifying distinct cloud shapes and combinations, such as Cirro-cumulus and Cumulo-stratus.

Types of Clouds. Image from Weatherstem website

As you can see in the above illustration, cirrus clouds are feathery, thin and wispy looking clouds that streak through the sky, often high up. Cumulus clouds (it would seem Constable’s favourite to paint) are puffy clouds that look like cauliflowers, often seen scattered throughout the sky. Whereas, stratus clouds are low and are uniform grey in colour, covering most or all of the sky.

When peering up to the sky, we all often spot shapes of things we know from their continuously changing forms. We love talking about the weather! Particularly in Britain, where the geography and the winds are so varied, and the airscape fluctuating; many of us come to associate these changes with our own moods and emotions.

There is a universal love for this canvas in the sky. The ‘Cloud Appreciation Society’ was founded in 2005 in the UK in response to a love of cloud beauty. The society seeks to appreciate and understand clouds, and with their worldwide membership showcase incredible cloud images, as well as exploring clouds in art, music, videos and poetry.

In art, the consciousness of clouds seems to have arisen particularly since the early Renaissance and came to a zenith in the eighteenth century. The most prestigious art institutions at this time, including the Royal Academy in London, ranked genres in order of importance. History scenes came first, portraiture second and landscapes were third.

Two hundred years ago, English artists JMW Turner (1775-1851), John Constable (1776-1837) and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), were radically paving the way for landscape painting to be respected as a primary genre. Their breathtaking works capture varied landscapes and weather conditions, prominently including cloudy skies. England was a perfect place for depicting different types of cloud formations being so… well, cloudy! The sun and clouds were essential for providing the invaluable light sources for their paintings also.

Cloud studies by John Constable, all c.1822. From the top: Study of Clouds, oil on paper (Frick Collection, New York),Study of Cirrus Clouds, oil on paper (V&A) and Cloud Study Stratocumulus Cloud, oil on paper.

According to meteorologists, John Constable was one of the few painters who conveyed cloud formations with realism and technical accuracy. In fact, he is known to have studied clouds so closely that sometimes meteorologists can even calculate the season and hour from his skies. It is a mystery how he achieved such accuracy, considering clouds can change shape quite rapidly.

By contrast, Royal Academy records show that Thomas Gainsborough often improvised his landscapes from models made up of stones, glass and even broccoli! This being said, it’s true that sometimes forms in nature can echo each other; broccoli or cauliflower can indeed resemble cumulus clouds, and in this way it seems Gainsborough was attempting to suggest something more universal.

Mr and Mrs Andrews, Thomas Gainsborough, c.1750, oil on canvas (The National Gallery). His dark, ominous clouds in the background foretell of things to come, not only rain and probably a storm, but they seem to add symbolic meaning to perhaps the mood of the sitters or indeed their relationship.

John Ruskin, the leading art critic and patron of the era, often talked of the beauty of clouds. He attempted to understand their form scientifically, but also their meaning in terms of affecting our mood. Ruskin was a fervent supporter of JMW Turner’s work, which (according to a publication by the Tate, ‘Five Things to know about Turner’) was frequently criticised at the time for being too controversial. Ruskin believed that artists should attain “truth to nature”, and that Turner achieved this through direct observation and understanding of the landscapes before him.

From top: Shields, on the River Tyne, JMW Turner, 1823. Watercolour on paper. Tate website. Flint Castle, JMW Turner, 1838. Watercolour on paper. Private collection, Japan, from abc gallery website.

Within Turner’s extremely prolific oeuvre of watercolours and oil paintings of landscapes, the depiction of the expanse of sky is paramount. It is clear he was concerned with the ever-changing drama of cloud and rain. When looking at his work, we get a real sense of the artist being perched at a certain spot, facing out to sea, watching the fantastic theatre of unpredictable weather and clouds beyond. The Tate website also records that it was believed Turner even asked sailors to tie him to a mast of a ship during an actual storm at sea, so he could paint a truthful account of being completely immersed in a tumultuous storm and the feelings it stirred within.

His passion for the sky in landscape painting evolved into dramatising the effect of clouds, and sun, on the whole environment, changing the direction of landscape painting.

John Ruskin’s Study of Clouds from Turner’s ‘Campo Santo, Venice’ which Ruskin owned. Illustrated in full below. Watercolour on paper (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).

Campo Santo Venice, JMW Turner, 1842, watercolour on paper (Toledo Museum, US).

Clouds have been a continuous source of inspiration for artists and, as we have seen, particularly for British painters, partly because the weather is often – some might say, so beautifully – cloudy in England.

More recently, and ironically, considering the once rigid hierarchy of genres at the RA, in 2016, British contemporary artist Tacita Dean had a major exhibition there called ‘Landscape’, which in part consisted of large scale drawings of clouds.

‘An ‘twere a cloud’, Tacita Dean, 2016. Spray chalk, gouache and charcoal pencil on slate

The smoky, hazy clouds draw you in, created with spray chalk, gouache and charcoal on slates once used in Victorian school rooms. Much of Tacita’s drawings are related to Shakespearean literature and letters; broken sentences and words are often faintly inscribed within these cloud works.

These pockets of water vapour will never cease to awe and amaze us, they are works of art in themselves, conjuring up thoughts and memories, reflections and projections; all we have to do is look up and dream…

“We believe that clouds are for dreamers and their contemplation benefits the soul.”

Cloud Appreciation Society

“A certain blue enters your soul”, Henri Matisse