A Celebration of the Sea

For the longest time, sea life has been a subject which has fascinated scientists and artists alike, who, through observation and analysis, have tried to understand more about the mystical creatures that reside in water.

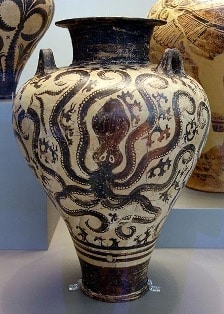

In Ancient Minoan civilisation, the manufacturing of pottery and ceramics was copious. Its production and acquisition was seen as a sign of wealth and power. Sea creatures were a popular subject matter for pottery in Minoan civilisations in what is now referred to as the ‘Marine style’.

‘The Marine style, perhaps, produced the most distinctive of all Minoan pottery with detailed, naturalistic depictions of octopi, argonauts, starfish, triton shells, sponges, coral, rocks and seaweed.’

A ceramic vase featuring an illustration of an octopus was found at the Palaikastro ruins in Crete. It is now located at The Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Greece and similar octopus vases can also be found in various locations around the world, including The Metropolitan Museum in New York and The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Mycenaean imitation of Minoan Marine ware, 15th century B.C.E. Tomb 2, Argive Prosymna

This particular vase is a ‘stirrup’ vase, a jar with two small handles at the neck of the vase. Stirrup vases were commonly used to hold and transport liquids, such as oil. These objects were made on a pottery wheel, and the handles and base would have been added by hand. The ceramicist would have used a dark coloured slip, a finely purified form of clay, to paint the illustration of the octopus.

The flowing body of the creature sits at the centre of the vessel. It’s eight tentacles dramatically curve around the surface, flowing in different directions. There is a fluidity to the lines, offering a playful sense of movement, as if the octopus is still floating around in the ocean. As we look at the cartoon-like style of this ancient image, it appears to give a contemporary feel.

Terracotta stirrup jar with octopus c. 1200–1100 B.C. On view at Met Museum, New York.

Jar with octopus motif, Late Minoan II Period (c. 1450 – c. 1400 BC). On view at Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

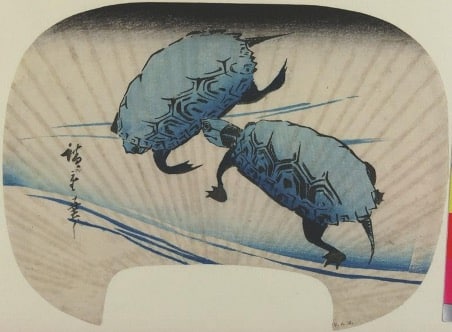

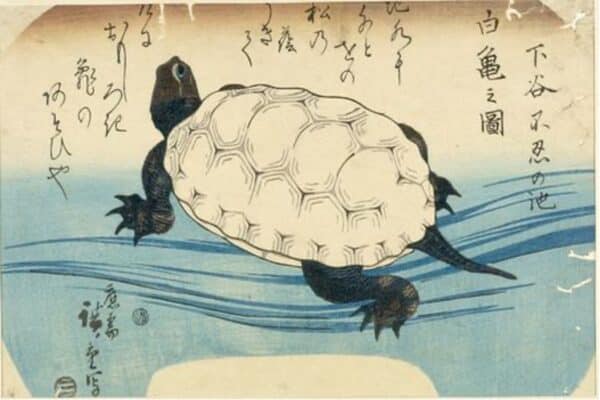

Three thousand years later in 1800, during the Edo period of Japan, a master of the Uyiko-e style, Utagawa Hiroshige, was creating beautifully intricate woodblock prints. Hiroshige made many prints of a variety of sea creatures including octopi, fish, lobster, crab and turtles. Below are two turtle prints by Hiroshige, both employing a blue and white colour palette.

They are designed for fans; in the first print you can see the rib marks of the fan and both prints use the layout design. In the first image, two turtles are swimming. Their shells are painted blue, their legs inky black. There is a feeling of movement created by the outstretched, bent legs of the turtle and the flowing lines of blue water behind them. The other Hiroshige print depicts a single turtle with a white shell, crawling over lines of blue. The indentations on the shell are delicately marked out with a fine brush.

From top: Swimming Turtles, Utagawa Hiroshige, c.1840-1842, colour print from woodblocks. In storage at V&A, London. A White Turtle at Shinoba Lake, Utagawa Hiroshige, 19th century, ink on paper. Harvard Art Museum.

The turtles seem to offer a sense of calm, perhaps due to their subdued colours, as well as the focus on more slower moving creatures. Turtles were symbols of longevity and good fortune in Japanese culture, as they were believed to live for 10,000 years.

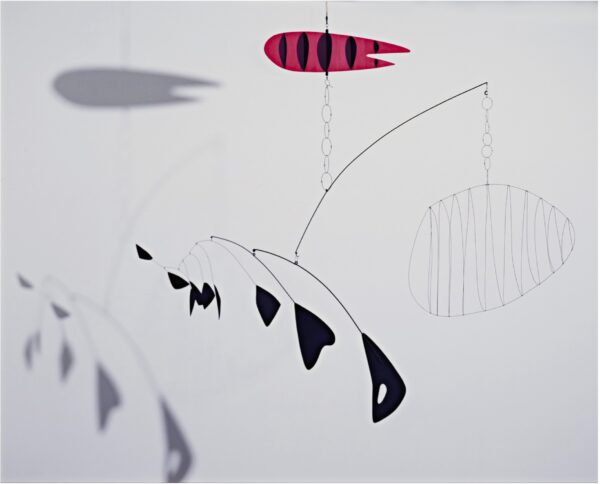

Roughly one hundred years after Hiroshige, the American sculptor Alexander Calder was working on his famous suspended wire mobiles. These innovative sculptures were meticulously designed, consisting of wire ‘arms’ with abstract forms cut from sheet metal, wire and wood. The forms float in air, interacting with space. A touch or slight breeze can move it and create an entirely new composition.

Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, Alexander Calder, 1939, sheet metal, Steel wire, Painted steel wire. The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In one of his early works, Calder looks to the ocean for inspiration. His ‘Lobster Trap and Fish Tail’ hung from the ceiling above the staircase in MOMA, New York. Its playful title refers to catching a lobster with a lobster trap or pot, where a fish is often used as bait. At the top of this mobile is a red striped organic form with two pointy edges, presumably representing the fish tail, and on another wire ‘arm’ sits a zigzag cage-like form made in wire, the trap. The mobile’s skeletal structure almost resembles fishing lines and hooks. Here, we observe a whole underwater scene taking place high up in the air.

There is something very lively to this sculpture, bringing to mind the cartoonish octopus from the Minoan vase that seems as though it may swim back to life. Calder draws in the air with his mobile. It dances around and undulates up and down, mimicking the gentle movements of the sea. Like Hiroshige’s turtles, Calder’s mobile asks us to slow down and look closely.

Each artist successfully brings something of the experience of the sea and its creatures to their work in such striking ways, as we can see in the images below. From these ancient to modern examples, there is a real playfulness to the depictions, and with them a tangible appreciation of the sea that stimulates the imagination and curiosity.

Wine Jar with Fish and Aquatic Plants, Unknown, 1279-1368. Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Ctenophorae, plate #27 from Ernst Haeckel’s ‘Art Forms of Nature’ published 1899. Image from Wikipedia.

The Gulf Stream, Winslow Homer, 1899. Oil paint on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Detail of Quinghua, Takashi Murakami, 2019. Acrylic on canvas mounted on aluminium frame. Photo: Josh White Courtesy Gagosian

With a love of the underwater world – that many of us were introduced to through the wonderful David Attenborough! – we celebrate this union of water flow and sea life in our Seabreeze collection of tablecloth and napkins.

Blue & White Company Seabreeze Tablecloth